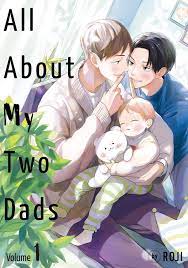

Any parent will tell you that being a parent is difficult. Every child is an individual, regardless of gender, sexual orientation, or if it’s your first or fifth child. Taking this truth and running with it, Roji’s All About My Two Dads follows Nao and Ai as they raise their son Hiro from birth until he turns eight years old in a (maybe) future Japan where same-sex couples are permitted to legally marry and adopt children. In the world of the narrative, these are relatively recent occurrences. Nao and Ai have been dating since college, and same-sex marriage was made legal during their time there. Taking advantage of that, the two later decide to adopt a child; Hiro is placed for adoption shortly after he is born. Despite the title, the story is really more about the two men’s struggles as they navigate the highs and lows of parenting a child.

The majority of the story concentrates around Hiro’s parents because he spends the majority of the volume as an infant and toddler (the final chapter jumps ahead five years to when he is eight years old). The most at ease of the two is Ai, who came out to his parents and friends with pride in middle school and has always been content with his identity. The biggest thing that bothers him is when people say that he “doesn’t seem gay;” Although AI is quick to point out that’s a damaging stereotype, he generally ignores these kinds of clashes, viewing them as the product of stupid people that he has to educate. Nao, on the other hand, resents the Othering of himself and his spouse and is far more sensitive to preconceptions and microaggressions. In one moment, despite Ai and Nao being two men, the grandmother of one of Hiro’s preschool buddies remarks on how nicely they are rearing Hiro. Ai dismisses her remarks, but Nao finds it offensive that rearing a child is based on a parent’s gender. He also wonders about how Hiro may be affected by this kind of discrimination when he gets older.

But this goes beyond the social commentary that a simpler work may have stuck with. Nao’s worries, however, stem not from his sexual orientation but rather from his early upbringing. His mother abandoned them for an undisclosed reason, and Nao was raised by his single father. (His father makes the comment that she “couldn’t live a normal life,” which may be interpreted in a number of ways. Nao interprets this to mean that she wasn’t interested in raising him.) As a result, Nao had to deal with the feeling of abandonment he still feels as an adult, in addition to growing up with only one parent who was the “wrong” gender (my word processor even attempted to auto-fill “single father” as “single mother”). This leads to significant concerns about his value as a parent, which serve as the plot’s central theme.

Irrespective of your sexual orientation or parenthood, Nao’s concerns are extremely relatable. He once has a dream in which his younger self says to him, “You’ve merely become older. “You didn’t grow up,” encapsulates his personality well. Nao is extremely sensitive to other people’s remarks because he believes that he is an imposter in his own life and that he is not worthy of being a parent or having a connection with his mother. She’s shocked that he interpreted it that way when he eventually tells someone that he feels othered by remarks about being one of two fathers; she meant to just say that all parents struggle while noting that he and Ai are both guys. This subplot asserts that having a kid does not negate your existence, and it is one of the book’s strongest points that Nao’s worries are acknowledged as normal aspects of life.

The story’s core still revolves around parenting, of course, and it’s done brilliantly. From casual remarks such as “He really provides us with everything. The story touches on many of the little moments in parenting that become pivotal points in life, from the joys of having school-age children to the men’s attempts to create a flowchart explaining why Hiro might be crying (much to Ai’s mother’s amusement) to the realization that snaps on baby clothes are evil. The storyline embraces the bittersweet aspects of parenthood while also acknowledging that it’s not always adorable and enjoyable and that it’s acceptable to feel like a horrible parent. A lot of the volume’s wholesomeness stems from the warm, familial vibe, which is really appealing. Though “wholesome” tends to conjure images of Wonder Bread-level blandness in families, Roji manages to make it work in this instance; while there are ups and downs, the most important thing is that everyone loves each other. This is made abundantly evident in the last chapter when eight-year-old Hiro writes a school essay about his family. He admits that others criticize his family for being unique, but he reassures them all that what counts is how much his fathers love him and each other.

Simply put, All About My Two Dads is a beautiful manga. Warm and endearing, it acknowledges the social and psychological problems of its people while still allowing them time to grow. Roji’s stated purpose of demonstrating that LGBTQIA+ individuals are just as regular as straight people is achieved in a non-preachy fashion with charming art and a compelling plot. This one is not to be missed if you’re searching for something endearing.