Chinese science fiction enthusiasts might be familiar with Cixin Liu, the Hugo Award–winning writer of the short tale that served as the basis for this manga. His book The Wandering Earth, which was adapted for the big screen in 2019, set a record for becoming the highest-grossing Chinese film ever made at home. Netflix quickly acquired the global streaming rights. His novel The Three-Body Problem is currently being adapted for a massive English-language TV budget by David Benioff and D. B. Weiss, the showrunners of Game of Thrones. To the best of my knowledge, this manga is the first English translation of a specific Liu story, and he is an emerging author.

Over the years, popular science fiction has found great inspiration in the notion of initial contact between humanity and an incredibly powerful spacefaring alien culture. I was too young to watch the groundbreaking TV miniseries V when it first aired in 1983, but I was impacted as a teenager by a rerun of the show in the late 1990s. There are parallels between Taking Care of God and the well-known 1953 book Childhood’s End by Arthur C. Clark in terms of themes and devices. When a world is abruptly forced to reevaluate its role in the cosmos, are the signs of this shift helpful or harmful?

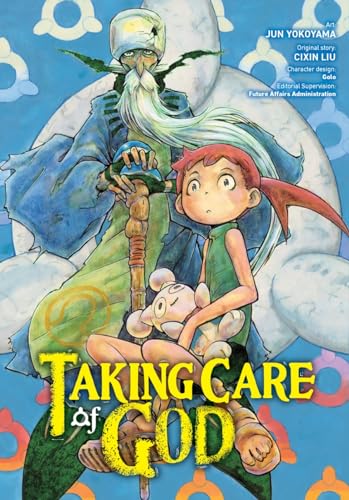

Zhihan, our primary point-of-view character, is a semi-feral second grader who lives in a small village with her mother and grandmother while her father works far away. She appears to be electively silent. Zhihan like to solve interpersonal conflicts by using severe violence a la Gremlin, followed by a fast escape. She’s wide-eyed, humorous, and prone to making stupid decisions—like throwing a rock at the head of an odd old guy who might be an omnipotent alien deity or scaling a dead tree that hangs over a steep gorge to get a bizarre doll.

When The Progenitors finally show up in large numbers, they make an agreement with the governments of Earth: in return for the amazing technology that powers their starships, they want to be taken care of when they get old. With humanity serving as their ready-made family to take care of them in their old age, the Progenitors created Earth as their retirement community. Except for Zhihan’s impoverished family, who view The Progenitors with distrust, individual household family units are financially encouraged with large subsidies to accept one or more Progenitors into their home. Many use the opportunity to make additional money.

Zhihan throws a rock at the elderly male Progenitor on their first encounter, but eventually Zhihan’s grandma gives in and lets him live with them. Though neither Zhihan nor her overburdened mother is excited with the idea at first, they eventually come to accept their strange new uncle into the family. He reminds me of the Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy’s ancient world-builder Slartibartfast.

The Progenitors adapt well to their new jobs as foster parents, aunts, or uncles at first, but when the money runs out, the narrative takes a darker turn. Ancestors are seized by force, put into government cars, and sent to unidentified locations. There have been more stories in the news about elder mistreatment, and some governments have proposed mass murders as a means of removing the overpopulation.

Taking Care of God looks at how people behave toward one another, first when they are given a reason to care and then when that reason is taken away. Although it makes sense that many people are wary of the newcomers, some of these reactions have a dark underbelly of racism and xenophobia. In the end, the majority of the personalities we interact with are merely people who learn to love and respect one another. Neither the Progenitors nor the majority of the families who grow close to them are evil people. Zhihan’s buddies battle valiantly to prevent their cherished “Grandmas” from being taken away by the government.

When Zhihan discovers, horrified, the results of her careless behavior, she regrets her naive violent outbursts. Her one and only line in the narrative is a tearful, sincere apology in a particularly moving moment. With a few exceptions where she purposefully obfuscates, her body language and facial expressions effectively convey her ideas despite her absence of vocalizations for the majority of the narrative.

Today’s industrialized nations face the daunting reality of rapidly aging populations around the world. This demographic time bomb already creates economic uncertainty in nations as diverse as the UK and Japan. When we have more elderly and disabled workers than healthy ones, what will we do? Do we support immigration from foreign nations? Do we encourage younger people to become parents earlier? Even more sinister possibilities have been explored by fiction, such as in Katsuhiro Ōtomo’s Roujin Z, where they forced euthanasia or confined the elderly in soulless, robotic hospital beds.

Taking Care of God, like the best science fiction, uses a fantastical scenario to shed light on the present or not too distant future. Will we respond hastily and fearfully, like Zhihan did at the start of the novel, or will we develop patience and humility while striving for greater goals? Although Liu’s solution resolves the issue without consulting Earth’s inhabitants, he raises important questions, and I want to see more of his work adapted with the same thoughtfulness and zeal.